Should California Penalize Big Oil for High Gas Prices?

California is no stranger to high gas prices, but a price spike this fall led Governor Newsom to accuse oil companies of ripping Californians off while raking in record profits. Who is to blame?

Today’s Debate

California is no stranger to high gas prices, but this year’s record-setting prices provoked California’s leadership to consider ways to either reduce prices or “refund” part of the money spent on gas prices directly to drivers. Republicans in the State Legislature proposed repealing the gas tax as early as January, which their counterparts from the Democratic party rejected in March.

Governor Newsom responded with a counterproposal a week later, proposing $9 billion in tax refunds to Californians in the form of $400 direct payments per vehicle:

“We’re taking immediate action to get money directly into the pockets of Californians who are facing higher gas prices as a direct result of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.”

In June, the state Assembly formed a committee - Select Committee on Gasoline Supply and Pricing - to investigate why California’s gas prices are so much higher than the rest of the country’s. On October 4, KCRA reported that select committee chair - Democrat Jacqui Irwin - announced they would be “releasing a report in the next few weeks.”

While we haven’t seen a report from the Select Committee, Newsom took actions into his own hands on September 30:

“We’re not going to stand by while greedy oil companies fleece Californians. Instead, I’m calling for a windfall tax to ensure excess oil profits go back to help millions of Californians who are getting ripped off.”

On December 5, at a special session of the Legislature he convened, Newsom unveiled what had morphed into a profit cap and price gouging penalty, asking the Legislature to enact a yet-to-be-determined “maximum gross gasoline refining margin” and to allow the California Energy Commission to impose a “price gouging penalty” for violations of the profit cap.

Leaders expect consideration of this proposal “to begin in earnest early next year.”

This brings us to today’s debate.

Argument in Brief

Should California penalize oil companies for profits earned this fall?

Gas prices spiked in California this August-October but they did not outside the western U.S.

At the same time, a key driver of gas prices - crude oil prices - went down

This led oil companies to earn very large profits

Oil companies have not provided sufficient explanation for high gas prices and record profits

Prices spiked because of acute reductions in refinery output

Low gas supply applied additional upward pressure on prices

California’s isolation from other U.S. energy sources limited its ability to respond

California is a difficult state to try to “fleece”

Oil companies need these profits to modernize the energy infrastructure

A tax or penalty would likely result in higher gas prices and more price spikes

The central question of this debate is whether the price spikes California experienced this fall were justified, unjustified but legal, or illegally achieved. While this is not an easy question to answer, given what we know now, I am inclined to believe they were justified. As a result, I believe the state should work with oil companies to make additional investments in the infrastructure we need to provide low-cost, reliable gas for the next 25 years rather than imposing a windfall tax as previously proposed or a price gouging penalty. This could involve a requirement that oil companies invest profits above a certain level back into California infrastructure.

Case For

Gas prices spiked in California this August-October but they did not outside the western U.S.

In his proclamation to the Legislature, Governor Newsom claimed that “Californians experienced some of the highest gasoline prices ever recorded in the State” during this 3-month period.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA),1 California gas prices dropped from $5.90 in July to $5.33 in August and then remained almost unchanged in September with an average price of $5.38. Both of these prices are below 2022’s running average of $5.49.

However, beginning in late September, prices began to rise leading October’s average gas price to hit $5.91, the second-highest monthly average on record.

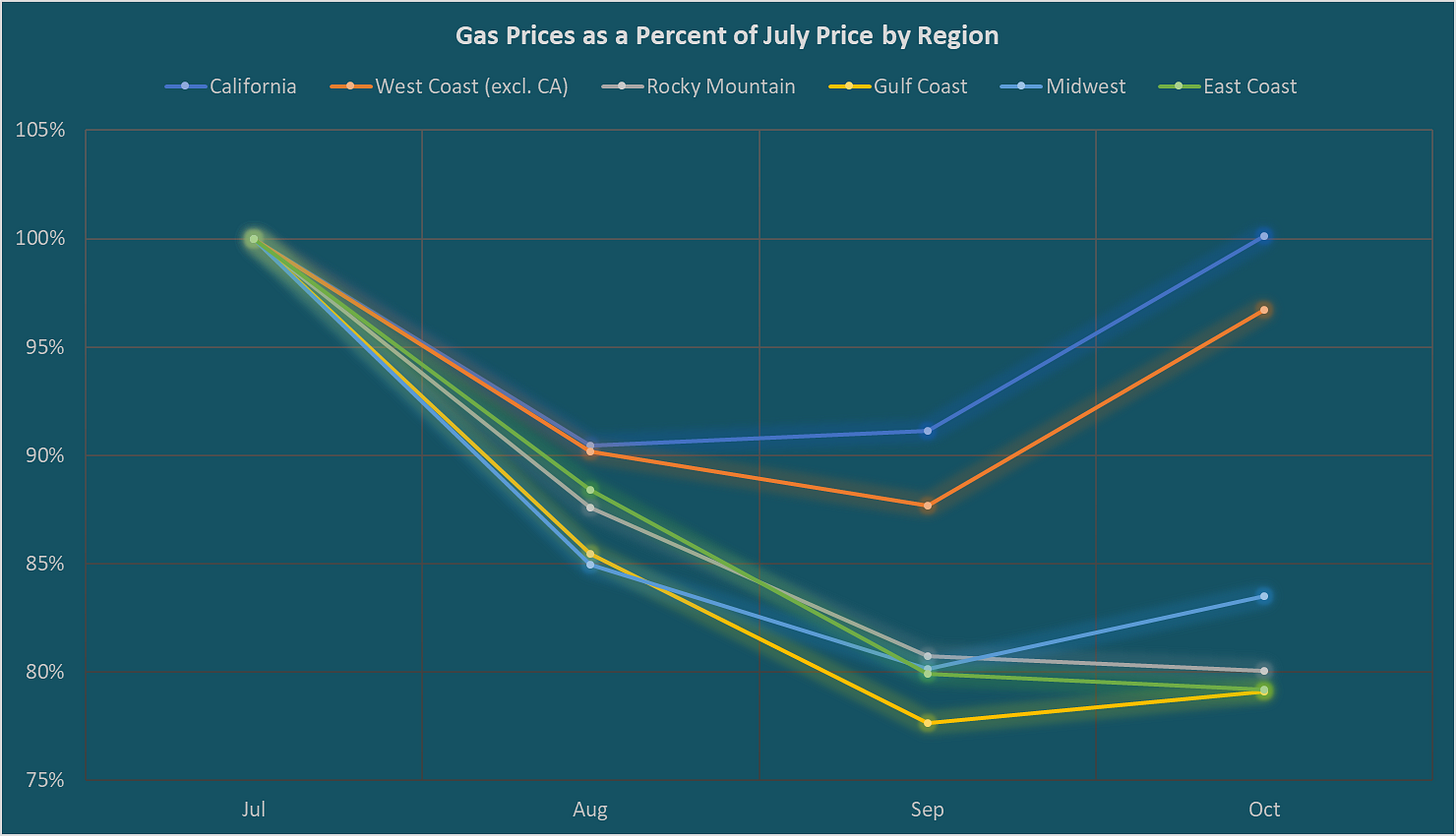

In contrast, the rest of the nation - except other West Coast states2 - saw steeper declines in August and then additional declines in September before seeing modest increases in October.

While October’s price change reflects an anomaly compared to the rest of the nation, it is not unusual for California’s gas prices to diverge from the national average. From 2000 to 2014, California gas prices went from roughly equal to the national average to about $0.50 above the national average. Over the last 8 years, the gap has grown significantly with California gas prices coming in a dollar more expensive than the national average in 2021. The other western states have experienced a similar, albeit smaller, divergence.

In summary, California could argue that its September and October gas prices were differentially elevated compared to the rest of the nation - except for the West Coast. However, the last 8 years have led to an increasing gap between California gas prices and the national average, making such a difference less exceptional.

At the same time, a key driver of gas prices - crude oil prices - went down

The price of gas consists of 4 costs:

Crude oil cost (the raw material)

Refinery cost (the process of converting the raw material into something useful)

Distribution/marketing cost (transporting it to the pump and selling it)

Government taxes/fees

Historically, crude oil cost has been the largest driver of gas prices, making up an average of 40% of the total price during the last 3 years.

This is why Governor Newsom made the following point on September 30 when announcing plans to consider a windfall tax:

“Crude oil prices are down but oil and gas companies have jacked up prices at the pump in California. This doesn’t add up.”

Newsom is right that crude oil prices were and are down from early this summer. Crude oil prices dropped 6% month-over-month in August, another 10% in September, and then another 1% in October.

So if price increases weren’t driven by increases in the price of crude oil, what led to the increases?

The chart below shows the four costs above per gallon of gas from July through October in California.

In September, there was a massive spike in refining costs/profits. Since 2020, refining costs/profits have made up an average of 26% of the total price of gas, but this jumped to 38% during the 4 weeks beginning the second week of September.

In summary, Newsom is right to say that crude oil prices went down. While this generally results in a decrease in gas prices, dramatic increases in refining costs/profits outweighed the decreases in crude oil prices.

This led oil companies to earn very large profits

Oil companies and refineries have reported significant revenue and net income figures during each of the first three quarters this year. Specifically, Newsom calls out the following 8 companies for their third-quarter earnings:

Phillips 66 profits jumped to $5.4 billion, a 1243% increase over last year’s $402 million;

BP posted $8.2 billion in profits, its second-highest on record, with $2.5 billion going toward share buybacks that benefit Wall Street investors;

Marathon Petroleum profits rose to $4.48 billion, a 545% increase over last year’s $694 million;

Valero’s $2.82 billion in profits that were 500% higher than the year before;

PBF Energy’s $1.06 billion that was 1700% higher than the year before;

Shell reported a $9.45 billion haul that sent $4 billion to shareholders for stock buybacks;

Exxon reported their highest-ever $19.7 billion in profits;

Chevron reported $11.2 billion in profits, their second-highest quarterly profit ever.

These figures represent the total revenue and income of multinational companies offering large suites of products and services. On the basis of that data alone, we can’t assume that those record-high figures were driven by California gasoline sales generally and by the specific spike in gas prices this fall.

However, Consumer Watchdog calculated the profits refineries made just in California, confirming Newsom’s point:

“The four big oil refiners who reported their West Coast profits – Marathon, PBF, Valero and Phillips 66 – together posted an average 73 cents per gallon profit in the 3rd quarter in the West. California oil refiners have only exceeded the 50 cent per gallon mark three times in the last twenty years…

PBF reported making 78 cents per gallon refining crude oil into gasoline in California in the third quarter– the greatest raw profits anywhere in the nation or world. By contrast, PBF's profits per gallon were 48 cents on the Gulf Coast, 49 cents per gallon on the East Coast, 55 cents per gallon in the Midwest – an average of 50 cents across the rest of America…”

Yet, looking at a single year only tells part of the story. In 2019, 2020, and 2021, these companies reported annual revenues less than their 2018 revenues. In fact, in 2020, collectively, they only brought in 57% of their 2018 revenue. They collectively lost $87 billion in 2020, making their average income over the last 5 years just two-thirds of their 2018 income. Even with substantial federal government funding as part of COVID relief, these companies experienced significant declines over the last few years.

Further, while scoring record profits may seem abusive, it’s important to view these financial figures in the context of other industries’ financial performance. Other industries have reported higher earnings since 2018.

Oil companies have not provided sufficient explanation for high gas prices and record profits

To determine if refineries have engaged in price gouging, the state needs to know if there was ample reason for the spike in refining costs. Newsom has repeatedly turned to oil companies to explain the price spike.

On September 30, Newsom said:

“Oil companies have failed to provide an explanation for the unprecedented divergence between prices in California compared to the national average.”

At the time, the California Energy Commission (CEC) sent a letter to industry executives:

“demanding immediate and comprehensive explanations for this inexplicable, unprecedented spike in gas prices within the past 10 days. This explanation must address the fact that there haven’t been any new state costs or regulations, that planned and unplanned maintenance typically does not result in large increases like this, and crude oil prices are down.”

The CEC also invited executives from five major oil refineries to explain what happened at a live hearing on November 29, but all of them declined to attend, sending letters explaining their perspectives instead.

Most refiners attributed their absence to legal reasons:

“The refiners all told state officials, almost two weeks ago, that they didn’t plan to attend, citing concerns that sharing information about their operations could violate federal antitrust laws that prohibit price-fixing and other anti-competitive practices.”

But PBF Energy offered a more direct explanation:

“The politicization of this issue by Governor Newsom, heightened by the misleading information he released and commented on related to our 3Q22 earnings, precludes us from participating in this hearing.”

Catherine Reheis-Boyd, president and CEO of the regional trade association, Western States Petroleum Association, offered a brief explanation, blaming anti-oil policies and supply shortages:

“The Governor and his Administration are failing to communicate what their policies actually cost Californians at the pump and how their decisions have led to the exact market conditions we have today. California faces a supply shortage as a result of repeated irresponsible policy decisions that have led to a lack of investment in refining capacity and necessary infrastructure, making California an energy island.”

But Governor Newsom did not find this rationale satisfactory:

“Oil companies have refused to provide complete and adequate explanations for their actions; WHEREAS the limited explanations refiners have offered, such as low inventory levels and overlapping scheduled maintenance schedules, can account for only part of the 2022 price spike and suggest the need for closer oversight of the refining sector to prevent supply shortages that artificially drive up prices…”

Is a supply shortage adequate justification for the price spikes? We’ll cover the argument blaming shortages next in the Case Against.

Case Against

Prices spiked because of acute reductions in refinery output

The law of supply and demand dictates that if the supply goes down while demand stays constant, the price goes up. This is the argument Anlleyn Venegas, a spokesperson for the Automobile Club of Southern California, used to explain high gas prices:

“Planned and unplanned refinery maintenance issues have tightened fuel supply in [California].”

The American Petroleum Institute made a similar point when responding to President Biden’s accusations of price gouging early this year:

“Gasoline prices are determined by market forces — not individual companies — and claims that the price at the pump is anything but a function of supply and demand are false.”

During the middle of September, 4 events reduced refining capacity on the following dates:

September 3-9

September 11

September 16

September 20

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), these outages resulted in a reduction of 3.5% in the four-week average of gross inputs to refineries from September 9 to October 7. From August 26 to September 23, California refineries saw a 5.1% decline in their four-week average throughput.

Was this reduction in refining throughput enough to drive refining prices and in turn, gas prices through the roof? This is a difficult question to answer well. Governor Newsom does not think so:

“Big oil keeps saying that one of the reasons gas prices are up is because of maintenance but… recent refinery maintenance impacted only 5.8% of California refineries’ supply. It doesn't add up.”

However, the EIA seems to think that output reductions could be responsible:

“Recent price movements for both products reflect how sensitive West Coast petroleum product prices are to relatively small changes in refinery output and import levels.”

California Energy Commission Chair David Hochschild echoes Newsom’s argument, contrasting this price spike with other historical price spikes:

“In September 2019, five refineries experienced unplanned maintenance issues, and California was faced with several refinery outages. The price spike was a mere 34 cents — a fraction of what Californians have been paying over the past week. Even the 2015 explosion at the ExxonMobil refinery in Torrance caused a price increase of only 46 cents per gallon, and the California Department of Justice deemed this price shock to be exacerbated by illegal price-fixing. So, refinery maintenance alone — especially prescheduled maintenance — cannot explain a sudden $1.54 increase in what refineries charge for every gallon of gas Californians buy.”

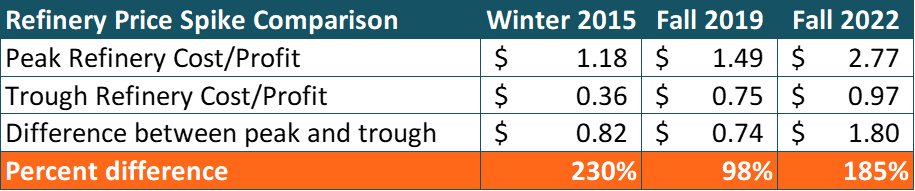

While these numbers do make the recent spike look like an outlier, it’s not fair to compare absolute dollars when gas prices have changed so much in the last 7 years. We need to compare the percent change from the peak of the refinery cost to its lowest point within the previous month. When we do this, we find that this year’s refinery price spike was twice as large as the fall 2019 spike but significantly smaller than the winter 2015 spike.

Further, while the 2015 price spike led to ongoing litigation with the state, the state has focused that case on price spikes that lasted almost 2 years, conceding that the defendants may not have caused the initial spike:

“During the relevant period (beginning at least as early as February 2015 and continuing into late 2016), Vitol and SK reached agreements with each other and with third parties in violation of California’s Cartwright Act… Defendants Vitol and SK may not have created the supply disruption that impacted California starting in February 2015...”

In 2015, refinery costs/profits went from $0.36 per gallon on February 2 to $1.18 on March 2 and then remained near or north of $1.00 for almost a full year. In contrast, refinery costs/profits spiked on October 3 of this year and by October 24, they had already dropped below their previous trough. On November 21, 2022, the refinery costs/profits per gallon dropped to the lowest level in almost 2 years.

Maybe this was because of political pressure or maybe they were able to resolve capacity and supply issues?

Low gas supply applied additional upward pressure on prices

The EIA’s point is especially true when supply is already low - as it was at the time of the price increases. Christopher Knittel, a professor of applied economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, seconds this perspective:

“Increases in the crack spread that we’ve seen recently has been just supply and demand.”

Crack spread is often used as a proxy for refiners’ profits because it represents the difference between gasoline prices and crude oil prices.

West Coast gasoline inventories decreased from the beginning of August to the end of September, falling significantly below their five-year (2017–2021) range.

“These low inventories may also have contributed to West Coast market conditions in which prices react strongly to relatively small changes in supply,” explains the EIA.

Record-low oil imports also contributed to an undesirable supply/demand curve for consumers. Over half (56.2%) of California’s oil supply comes from foreign sources. As shown in the chart below, imports zeroed out in early September, reducing the amount of oil available to refine.

Could these 3 variables combine to drive up gas prices by 10% from September to October in California while gas prices increased only 3% nationally?

Experts, like Amy Myers Jaffe, the managing director of Tufts University Climate Policy Lab and a former executive director for energy and sustainability at UC Davis, have been warning that low supply moments can cause severe spikes in gas prices like this for years:

“[Other countries] don’t wait for the trading community to find it profitable to hold inventory, they require refineries to hold a minimum level of inventory. For a decade, I’ve been saying we need to do that in the United States, and I certainly said that it needs to be a requirement for the state of California.”

California’s isolation from other U.S. energy sources limited its ability to respond

These low supply problems are exacerbated and extended because California can’t open the spigot to oil from the Gulf Coast states or other domestic sources when we’re running low. WSPA President and CEO Catherine Reheis-Boyd describes California as an “energy island” for 3 primary reasons:

State regulators require different gasoline than the rest of the country

Our refineries refine a heavier crude oil than the Gulf Coast crude oil so California’s refineries cannot use Gulf Coast crude oil

There aren’t pipelines to transport fuel to California from other states

This severely limits California’s ability to course-correct when refining output drops and inventories are low, as the EIA explains:

“Consequently, the West Coast generally must maintain steady refinery runs to ensure regional supply meets demand, and any refinery outages can disrupt this balance. Furthermore, when refinery outages occur, West Coast markets must draw down local inventories or import product from refineries in Asia to meet demand because of the different fuel specifications.”

California’s declining refining capacity may also reduce our ability to respond to disruptions. The number of operating refineries in California has dropped from 40 in 1983 to just 13 this year, corresponding with a 30% decline in total refinery capacity. Valero vice president Scott Folwarkow explained why this is happening in a letter to the state Energy Commission:

“California policy makers have knowingly adopted policies with the expressed intent of eliminating the refinery sector. California requires refiners to pay very high carbon cap and trade fees and burdened gasoline with cost of the low carbon fuel standards. With the backdrop of these policies, not surprisingly, California has seen refineries completely close or shut down major units. When you shut down refinery operations, you limit the resilience of the supply chain.”

In summary, acute reductions in refinery capacity coupled with already low supply, low imports, and a stripped-down refining industry likely explain the gas price spikes this fall.

California is a difficult state to try to “fleece”

If oil companies were interested in ripping off consumers in a state, there are several reasons why they would likely avoid California. The first is that California is openly hostile to oil companies, suggesting that the state would have no qualms about penalizing oil companies. The American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers explains the industry’s relationship with the state this way:

“Hostile policies and rhetoric have also contributed to a difficult production environment for liquid fuel producers.”

Second, and more directly, California Attorney General Rob Bonta put oil companies on notice on March 18 when his office sent all refiners a letter:

“During this turbulent time, I want to warn oil refineries against taking advantage of the current market disruption. My office is currently litigating against multinational gas trading firms SK Energy Americas and Vitol for anticompetitive conduct, we are closely monitoring the market, and we will not hesitate to take action against others if they violate the law.”

The ongoing litigation against the gas trading firms and the creation of the Legislature’s select committee to investigate high gas prices would also likely dissuade refineries from trying to deceive the state. Would oil companies really try to rip off Californians amidst all the scrutiny and track record of litigation and hostility?

It seems unlikely, but one could argue that California’s hostility makes it easier for oil companies to blame gas price spikes on policy and regulatory issues or even that oil companies are out for revenge, as Consumer Watchdog argues:

“[The oil and gas industry] has declared war on the state of California and is raising prices unreasonably to punish the public and lawmakers for enacting tough new (environmental) laws.”

Oil companies need these profits to modernize the energy infrastructure

Given recent losses, aging infrastructure, and increased costs associated with updating infrastructure to meet new climate goals, oil companies could argue that they need these profits to prepare us for a more reliable energy future. One of California’s refiners, PBF Energy, makes this case in its letter to the state Energy Commission:

“Refining is an extremely capital-intensive business."

PBF also explained that it is using this year’s record profits to pay off “exorbitant debt” accumulated during COVID.

While PBF may be using these profits to pay off debt, a Wall Street Journal analysis showed most are not:

“Oil prices are at their highest in years and politicians want companies to pump more. But most large American frackers are standing pat, or even letting production decline, and instead are handing investors cash… Nine of the largest U.S. oil producers this week said they shelled out a combined $9.4 billion to shareholders via dividends and share repurchases in the first quarter, about 54% more than they invested in new oil developments.”

A tax or penalty would likely result in higher gas prices and more price spikes

Imposing a new tax or price gouging penalty - whether justified or not - may have the unintended consequence of increasing gas prices and causing more price spikes.

In their letter to the state Energy Commission, executives from Valero warned that adding costs, such as a new tax, “will only further strain the fuel market and adversely impact refiners and ultimately those costs will pass to California consumers.”

In addition to causing price increases directly, another refiner explained the potential effect on future investments:

“California's regulatory environment is putting future investment in refining and fuel manufacturing at risk in the state.”

And this is likely to lead to more problems as Gregory Brew, a historian of oil and a postdoctoral fellow at the Jackson School of Global Affairs at Yale University explains:

“California has long discouraged local fossil fuel production to protect the environment, with processing now increasingly reliant on an array of aging refineries… These facilities’ infrastructure is aging — several refineries have been operating for more than a century — and production is interrupted when machinery fails.”

My Assessment

This is a very complicated issue, which is likely why - in part - California has been trying to solve this problem for over 2 decades without much progress.

“California officials have had repeated warnings over the last two decades that the state’s unique blend of gasoline is susceptible to supply shortages and sharp price spikes. But despite multiple reports and special committees, California has struggled to find solutions as it tries to rapidly reduce its reliance on fossil fuels.”

While I can’t offer a comprehensive solution here, I can evaluate the proposals under discussion. To do so, it’s important to distinguish between the windfall tax and the price gouging penalty.

To make the case for a windfall tax, the state only needs to make the case that oil companies made unusually large profits off of their activities in California. Consumer Watchdog has already done this using these companies’ publicly reported data.

This does not, however, mean that a windfall tax is a good idea. Comparing the earnings of the oil and gas industry to earnings in other industries casts immediate doubt on the idea that oil companies are raking in greater profits than companies in other industries. Why charge oil companies a windfall tax if we’re not going to do the same for other industries - especially those that benefited greatly from pandemic-induced lockdowns? Not only that, but it feels hard to justify stripping a portion of the profit from these companies after years of government-ordered lockdowns produced significant losses for them.

Price gouging is a different story because it implies that refining companies intentionally manipulated the market to benefit their shareholders. This is illegal. If the state actually believes this is what these companies did, then the California Department of Justice should launch an investigation, as they did for the 2015 gas price spike scenario.

While it’s impossible to know, at this point, if those companies engaged in market manipulation, the reasons they offer for the price spikes seem reasonable. In fact, experts on all sides of the debate have been warning the state about the potential for price spikes for these very reasons for decades.

Further, Ed Hirs, an energy fellow for the University of Houston, says “he’s seen no hard evidence of price gouging during this spike” and argues that the state would need to engage in “some serious research” before being able to claim refineries gouged prices. A federal judge in San Diego just dismissed a class-action lawsuit accusing major oil companies of colluding to keep fuel costs artificially high, demonstrating the legal challenges for such an allegation.

Rather than spend time and money on such an investigation, I believe the state should make additional investments in the infrastructure we need to provide low-cost, reliable gasoline for the next 25 years (even though new gas-powered vehicles will not be sold by 2035, many people will still drive used gas-powered vehicles). Any new tax or penalty that could come from such an investigation would likely have the opposite effect anyway: higher gas prices in California over the long term and reduced investment in our energy infrastructure.

Given the dire needs of the California infrastructure, it seems unfortunate that oil companies’ record profits are ending up primarily in the pockets of investors - and not in additional investments in infrastructure. Perhaps, the state could require oil companies to invest profits above a certain level back into California infrastructure rather than pushing to put oil profits in the state’s coffers.

Note: If you use data from California’s Energy Commission, you’ll find slightly different averages, though both datasets show the same trends.

Oregon, Washington, Arizona, Nevada, Hawaii, and Alaska