Should California Give $300M to High-Need Schools?

Despite significant changes in how the state allocates funding to schools beginning in 2013, the achievement gap has remained large. Could another $300M help or will something else close the gap?

Today’s Debate

California’s public education performance needs improvement. The state ranks 40th in pre-K through 12th grade education, according to US News 2022 rankings. On average, 86% of California students graduate high school compared to 92% in Florida and 94% in Texas.

Performance in the earlier grades is worse. Almost 70% of 4th graders are not achieving proficient scores in math or reading. In 2022, California was one of 15 states performing significantly below the national average for 4th-grade math.

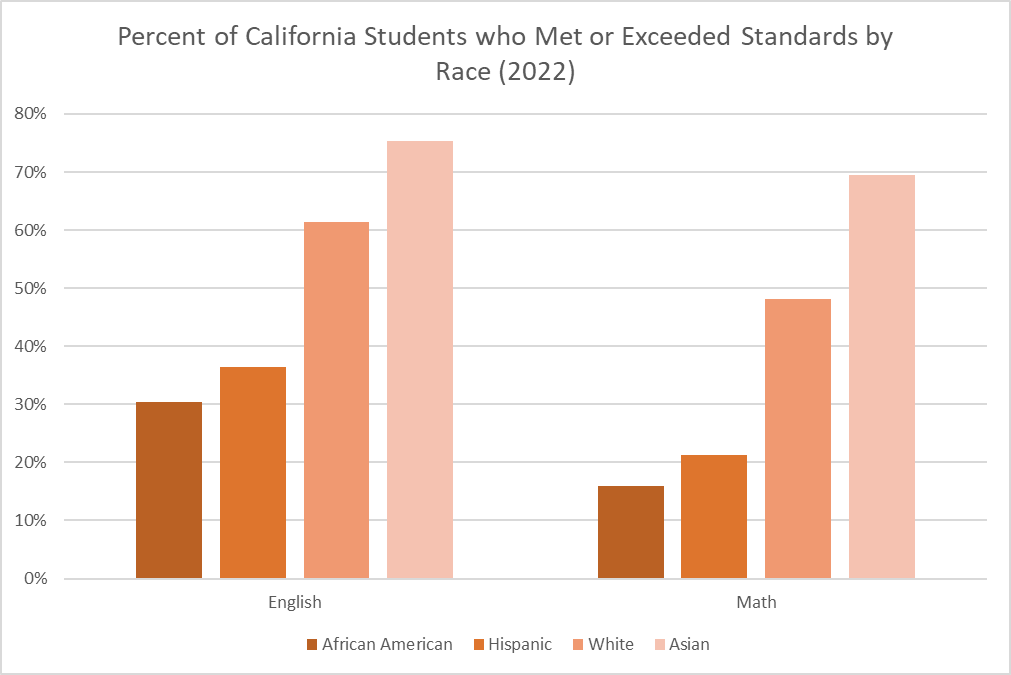

Test scores for non-white and non-Asian populations and for low-income students are much lower than the state averages. This difference in academic performance is called the achievement gap. The achievement gap can refer to the difference in educational achievement between either high-income and low-income students or white students and black or Latino students. In California, the achievement gap is stark on both of these dimensions.

Closing the achievement gap has been a major educational priority and topic of debate in California and around the country for over a decade. In the fall of 2022, Assembly Member Akilah Weber proposed directing more funding to the lowest-performing students in the state by making changes to what is known as the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). LCFF dictates how the vast majority of state funding is allocated to school districts. Weber’s hope was that this would help close the black-white achievement gap since many black students are currently among the lowest-performing students in the state.

But Governor Newsom asked her to withdraw this bill, promising to include something similar in his 2023 budget. And he did, kind of. He allocated $300M to what he has called high-need schools (elementary and middle schools where at least 90% of students qualify for free or reduced-price meals, and high schools where at least 85% qualify), arguing that most low-performing students go to high-need schools and that re-allocating funds in the way Assembly Member Weber suggested may present legal challenges.

Newsom is calling this new allocation of funds an “Equity Multiplier” because it is supposed to shrink the achievement gap. Will it? That is the debate for today.

Argument in Brief

Should California allocate an additional $300M to high-need schools to help close the achievement gap?

California’s achievement gap requires addressing because it is large and growing

Most of the lowest-performing students go to the high-need schools identified by Newsom

Giving more money to these schools will drive up student achievement

We already tried this and it hasn’t worked

The money won’t be spent in ways that drive academic improvement

The equity multiplier doesn’t address the root causes of the achievement gap

California’s achievement gap is large, leading California to find itself in the bottom 20% of states in public education outcomes. The $300M proposed by Newsom is a drop in the bucket compared to the overall education budget, so it is unlikely to have a dramatic impact on the achievement gap.

However, directing more funds to high-need schools - as the state has been doing since 2013 - seems to be having an effect, albeit smaller than desired. California should move forward with this targeted funding for high-need schools while increasing transparency and accountability to ensure as much money as possible goes toward benefiting the highest-need students.

Case For:

California’s achievement gap requires addressing because it is large and growing

In 2022, white students were more than twice as likely as black students to be meeting English/Language Arts standards and three times more likely to be meeting math standards, according to the state’s California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress, or CAASPP.

The achievement gap along socioeconomic lines is similar in magnitude. Students not considered to be economically disadvantaged were 1.8 times more likely to be meeting English standards than their economically disadvantaged peers and 2.4 times more likely to be meeting math standards.

The achievement gap has held relatively constant over the last 15 years with some variation by race/ethnicity:

“Moreover, we find that average test score disparities between non-poor and poor students and between White and Black students are growing; those between White and Hispanic students are shrinking.”

The achievement gap matters in 4th-grade test scores because it has long-term consequences, as sociologist Christopher Jencks explains:

“Reducing the test score gap is probably both necessary and sufficient for substantially reducing racial inequalities in education attainment and earnings.”

While the achievement gap between white and Hispanic students is similar in size to the gap between white and African American students, the former has a much larger influence on California’s overall education scores because Hispanic students represent the majority of California public school students:

Most of the lowest-performing students go to the high-need schools identified by Newsom

In Newsom’s budget proposal, he stipulated that Equity Multiplier funding would go to schools with at least 85% (high schools) or 90% (elementary and middle schools) of the student population qualifying for free or reduced lunch. To qualify for free school meals, a household of 4 must make under $36,075, and to qualify for reduced-price meals and snacks, a household of 4 must make under $51,338.

It intuitively makes sense that children in low-income households would perform worse in school - and the data shared above established that economically disadvantaged students are underperforming their economically advantaged peers by roughly a 2 to 1 ratio.

However, some advocates of Assembly Member Weber’s original bill argue that this won’t benefit many of the black students needing extra help:

“It sounds good, but it doesn’t actually get to the students who need the help. This is an apple, and what we wanted was an orange.”

This is a surprising claim because I’d expect many of the low-performing black students also to be part of low-income households. But a CalMatters analysis found that less than 26% of California’s black students are in schools that will qualify for the Equity Multiplier. This doesn’t mean that the students who do qualify won’t need help, but it does suggest, surprisingly, that most black students are not in “high-need” schools.

This is shocking, given the racial wealth gap. Over 28% of black children in California are living in poverty, compared to 17% of all children.

However, black students make up just 5% of the full student population. As a result, Newsom’s eligibility requirements could include the vast majority of low-performing students and still not include the majority of black students because they represent such a small portion of the total. This would imply that there is a sizable portion of economically disadvantaged black students who happen to be in schools that are not predominantly economically disadvantaged.

Interestingly, this has forced a decision between targeting extra funds to black students (who are, on average, the furthest behind) and targeting extra funds to low-income students (who are almost just as far behind). If your goal is to improve the state’s scores the most, Newsom’s focus on low-income students likely makes sense. Almost 60% of California students qualify for free or reduced lunch, while just 5% of the student population is black.

Newsom’s office offers another reason for his choice:

“Weber’s office and the bill’s sponsors said Newsom raised concerns about violating the state’s Proposition 209 and the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. The former prohibits preferential treatment of an racial or ethnic group and the latter guarantees equal protection for all citizens.”

Christina Laster, a co-sponsor of Weber’s bill argues that this is not a real obstacle:

“It was never once a racial thing. It’s about the category rather than who’s in the category… If after one or two years those students were progressing, it could be any other student group that could be considered.”

Giving more money to these schools will drive up student achievement

Regardless of whether you agree with Newsom’s target population or Weber’s, there remains an all-important question of whether this extra funding will actually help at all. In answering this question, it’s important to start with how much California spends on public education relative to other states. If it spends a lot more than other states while getting worse outcomes, then even if extra money might help, other states’ relative cost-effectiveness would demonstrate that there are other more cost-efficient ways to improve outcomes.

California currently ranks 19th in public education spending and funding, spending $13,642 per pupil*. The state’s education funding increased by 50% between 2017-18 and 2021-22, pushing California’s education spending above the national average after many years of what some call significant underfunding. California also has a higher cost of living than most other states. When adjusted for differences in labor costs, California’s rank drops to 35th. Further, when you compare the relative effort index for public education funding (education funding as a percent of state GDP) in California to the historic national standard of 4.0%, California is more than 25% below.

All these taken together puts California in the middle of the pack, if not slightly below average in spending. California could spend more money on education.

More spending does seem to be associated with better academic outcomes. The Learning Policy Institute's review of studies on this topic finds:

“Recent studies have invariably found a positive, statistically significant relationship between student achievement gains and financial inputs.”

And the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) agrees:

“Although policymakers and researchers have long debated the relationship between school spending and student outcomes, recent research using better data and statistical techniques has consistently documented a causal link between increased funding and improved student outcomes.”

But even if this correlation is generally true, it doesn’t mean that spending incrementally more in targeted districts would impact academic achievement in those schools.

However, a natural experiment occurred in California when the state implemented the Local Control Funding Formula in 2013. LCFF allocates funds based on pupil needs and eliminates many limitations on the use of funds, allowing “local control” over spending decisions. In addition to base grants, which are based on Average Daily Attendance and grade level, local education agencies receive “supplemental” and “concentration” grants, based on the number and percentage of English language learners, students in foster care, and students from low-income families.

Researchers found that funding redistribution created by LCFF led to a meaningful impact on student performance:

“We find that LCFF-induced increases in school spending led to significant increases in high school graduation rates and academic achievement, particularly among poor and minority students. A $1,000 increase in district per-pupil spending experienced in grades 10-12 leads to a 5.9 percentage-point increase in high school graduation rates on average among all children, with similar effects by race and poverty. On average among poor children, a $1,000 increase in district per-pupil spending experienced in 8th through 11th grades leads to a 0.19 standard-deviation increase in math test scores, and a 0.08 standard-deviation increase in reading test scores in 11th grade.”

Research on the effect of education funding redistribution in 4 other states led to similar recommendations.

Case Against:

We already tried this and it hasn’t worked

The Equity Multiplier is, as the name suggests, a multiplier - rather than a new idea. LCFF, which was adopted in 2013, was designed to do the very thing the Equity Multiplier intends to increase - divert more funding to the students (and schools) who need it most.

LCFF is the largest single source of education funding and it has increased significantly over the last few years.

Local education agencies (school districts and charter schools) receive “supplemental” and “concentration” grants, based on the number and percentage of English language learners, students in foster care, and students from low-income families. Dan Walters of CalMatters suggests that this progressive funding approach hasn’t yielded the desired results:

“So far, the disparity has resisted inconsistent efforts by the state to close it, most prominently by giving schools with larger numbers of at-risk students extra money for focused instruction.”

This is despite the fact that LCFF has resulted in more funding for disadvantaged student populations:

“Under LCFF, 2020–21 per student spending is higher for low-income than higher-income students (by $1,265), for English Learners (ELs) than non-ELs (by $500), and higher for Black and Latino than white students (by $1,278 and $1,185, respectively).”

The following charts show that African American and Latino students receive more per-student funding, as do lower-performing students:

Spending per student segmented by academic performance

Heather Hough, director of Policy Analysis for California Education, also believes that these extra funds haven’t worked:

“What we have been doing has not worked. We’ve been talking about accelerated learning, but we have no experience with accelerated learning, and our track record with closing the achievement gap is not good. … We cannot revert to business as usual because that did not work. This requires large-scale, systemic change.”

But an extensive analysis by the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) seems to dispute Hough’s claim:

“When evaluated across districts—especially when focusing on the highest-need districts—LCFF has led to a more equitable distribution of funding and outcomes. Spending has increased fastest in the highest-need districts, leading to a relative rise in graduation rates and test scores; additional concentration grant funding appears to raise A–G completion rates at districts that received the most funding; and due to concentration grant funding, standardized test scores improved in these districts at a magnitude consistent with prior research.”

These gains in student performance have led to a shrinking of the achievement gap between districts, which is expected to continue:

“Furthermore, the relative increase in funding of $2,000 per year for highest-need districts could close test score gaps across districts—but not across students—within the next decade, if effects do not diminish over time or have not widened substantially during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

The achievement gap between different groups of students (e.g., different racial groups and different socio-economic groups) has been more resistant to change than the gap between districts, at least in part because school districts - which possess significant authority over how LCFF funds are distributed - have not distributed funds according to the proportion of high-need students in each school as much as they could have. I’ll explore this in the next section.

In addition, when you add in all other funding schools receive, the funding advantage high-need schools have from LCFF almost disappears:

“Thus, while LCFF represents an unprecedented shift in California school finance towards more equitable funding based on student need (Putnam-Walkerly and Russell 2014), when we include formula and non-formula revenue sources, it has generated only modestly greater increases in spending progressivity than those that existed before the recession.”

The money won’t be spent in ways that drive academic improvement

Schools received $190B from the federal government as COVID relief in 2020 and 2021, and now 2-3 years later, only 55% of the funds California has received have been spent, according to the U.S. Department of Education. Examples like this cause people to worry that funding given to schools will not be spent in the way it was intended.

Dan Walters of CalMatters agrees, arguing that more oversight is necessary:

“Giving poor districts such as Merced more money is one obvious response, but the Legislature should insist on better oversight on how extra money is spent and also accept that there’s more to the equation than money.”

And there are LCFF-related cases to support Walters’ suspicion:

“In 2015, the ACLU sued the Los Angeles Unified School District for failing to spend the money generated by English learners, foster children and low-income students on services for those groups. In 2021, the California Department of Education found that three school districts in San Bernardino County misused funds for high-needs students.”

There are 2 ways that Newsom’s $300M could be misspent - and that LCFF funds, more generally, could be misspent. First, they could be spent on the wrong schools and the wrong students, as PPIC explains:

“While the funding formula targets districtwide need, it does not explicitly allocate these dollars to the students or schools that generate this additional district funding. If districts spend their supplemental and concentration grant funding only on high-need students, then any distinction between district- and school-level (or even student-level) funding is unimportant. However, if districts spend equally on all of their students, then it limits the ability of the LCFF formula to distribute spending progressively. There are numerous examples that suggest that districts may not be fully targeting LCFF dollars.”

How often are school districts spreading their total LCFF allotment evenly between schools vs. distributing them according to need? A PPIC analysis found that for each LCFF supplemental and concentration dollar generated by a school (i.e., by having high-need kids in their school), its site-level spending increased by only $0.55. This suggests that most districts could be distributing almost twice the LCFF supplemental and concentration grant funding to high-need schools.

Secondly, districts and schools themselves could also spend these funds on the wrong interventions.

“Higher-need districts increased spending on salaries for pupil services and other support staff besides teachers and administrators (e.g., nurses, counselors, teachers’ aides) more than lower-need districts… Notably, the largest spending increases were in the category of staff benefits, the result of multiple factors.”

It’s hard to know if high-need districts are spending the right amounts on each of these categories because the evidence around what interventions make a difference is, as summarized above, rather mixed, and districts face some constraints around how they spend on benefits and staff.

What we do know is that transparency and accountability could increase:

“Local Control and Accountability Plans are intended to account for the funding and services provided for high-need students, but these are often incomplete and unclear, making it difficult to use them to understand how districts use supplemental and concentration funds.”

The equity multiplier doesn’t address the root causes of the achievement gap

While much of the conversation about the achievement gap focuses on K-12 education, this is not where it begins:

“The gap between whites and blacks is present before children experience any schooling. By the time children are three or four, it is already a standard deviation.”

It turns out that school has less of an impact on the achievement gap than one would expect:

“Does the gap increase while students are in school? The surprising answer is no. Researchers have found that the rate of growth in achievement among blacks is equal to that among whites during the academic year. In the summertime, both groups show a decrease, but that decrease is larger for blacks than for whites. So while the achievement gap doesn’t increase while students are in school, it doesn’t decrease either.”

If differences in home life and community opportunities both create the achievement gap and perpetuate it, would it make more sense to focus our efforts there rather than on the public education system? Maybe, but education is one of the state government’s primary responsibilities and largest budgetary item, so it also makes sense to leverage its resources to try to address this problem.

What factors actually predict achievement gap magnitude?

“Racial/ethnic segregation is one of the strongest predictors of racial/ethnic achievement disparities, primarily due to the disproportionate concentration of Black and Hispanic students in high-poverty schools... Further, while racial/ethnic school segregation may not have changed much, socioeconomic school segregation has grown substantially since the 1980s.”

Stanford researchers cite a number of conditions that are associated with a shrinking achievement gap:

“While we do not have definitive evidence regarding the best way to achieve this synergistic pattern, our analysis points to several common factors associated with improving achievement. In other words, districts with more experienced and present teachers—and where those teachers are more equitably distributed—tend to be the districts where both achievement and equity are improving the most.”

Heather Hough, who was cited earlier, also points to teachers and other support staff as key to closing the gap:

“The state’s recent infusion of money into K-12 schools will likely not be enough. The changes need to be widespread and long-lasting, particularly regarding staffing. Prospective school counselors, for example, need to know their jobs will exist a decade from now.”

However, the Stanford researchers cited above indicate that this explains just a small percentage of the variation in the gap:

“Our models account for, at best, only about one-sixth of the variation in trends among districts, indicating that there are many other factors at work.”

Increased spending could help - particularly if it’s directed at increasing teacher quality, performance, and tenure - but this will likely still only address a small portion of the root causes of the existing achievement gap.

My Assessment

Closing the achievement gap has “resisted” years of effort by governments and nonprofits across the nation. Another $300M aimed somewhat vaguely in its direction is not going to make a dramatic difference. In fact, $300M is just 0.2% of the overall K-12 state spending and 0.4% of LCFF funding.

That said, it might help some and in the absence of other evidence-based, cost-effective strategies for closing the achievement gap, it likely makes sense to pursue it. The LCFF experiment of the last 5-10 years seems to show that distributing more money to high-need school districts shrinks the gap. This is consistent with a larger body of research that consistently associates higher per-student spending with better academic outcomes.

There also appear to be tweaks California can make to the Equity Multiplier based on lessons from LCFF. Namely, the state should work with districts to get their funds distributed more progressively to the schools in the district, and it should increase transparency and accountability around how the funds are spent.

That said, if we really want to close the gap, we’ll likely need a more comprehensive strategy that adequately addresses the issues outside of the school that seem to cause and then perpetuate the gap. It’s possible that the Governor’s Community Schools strategy - “an effort to ensure that students and families in local communities can get the resources they need at their school to thrive in the classroom” - is the answer or at least part of the answer to the social and familial issues that undermine academic achievement.

While more holistic approaches are developed, as Assembly Member Weber said in her statement on Governor Newsom’s budget, “I believe this proposal is a step in the right direction.”

Having been a teacher of elementary age children, it seems to me that the parents of the lowest performing children are suffering economically, which has many effects on the educational performance of the children. Number 1 solution is to raise the minimum wage to $20/hr and/or provide a universal guaranteed income for all. You can figure what that will achieve on many fronts.